Marriage and 'Gender Identity' Before European Rights Court

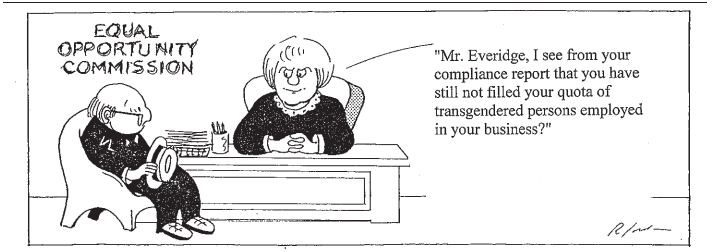

An Illustration of Difficulties Arising From Double Definition of Sex

by Grégor Puppinck, director, European Centre for Law and Justice (Abridged from Zenit.org)

On April 29, 2013, the European Court of Human Rights decided to refer the case H. v. Finland (N°37359/09) to the Grand Chamber, i.e. the highest formation of the Court, in order to conduct a retrial. This whole affair, which gave rise to a European Court’s Section’s judgment on 11/3/2012 involves Finland’s refusal to legally recognize the sex change of a person married to someone of a biologically different sex, conditioned on his first obtaining a divorce. In the Section’s judgment, the Court noted “that in essence the problem in the present case is caused by the fact that Finnish law does not allow same-sex marriages.” (§ 66)

The applicant was born male in 1963; however, experiencing the feeling of belonging to the opposite sex, he changed his name in 2006. Even before he underwent a sex change operation in 2009, in 2007 he applied for a new identity number, seeking to indicate in his official documents that he was of the feminine sex. This request was rejected by the public authorities. They based their decision on the fact that it is impossible for two women to be married in Finland, and therefore it was appropriate that the applicant's marriage first be dissolved. The applicant refused to conform to this formality and since the Finnish administrative courts have upheld the decision of the public authority, the applicant has subsequently decided to bring the case before the European Court of Human Rights, hoping to have Finland condemned. In his view, the obligation to first divorce his wife, or to transform his marriage into a civil partnership, before being accorded full recognition of his new gender was a violation of his rights, in particular those derived from Articles 8 (right to respect for private and family life) and 14 (prohibition of discrimination).

In a judgment in November 2012, the Fourth Section of the Court unanimously rejected the application. The Court certainly considered that Finland’s refusal to grant full legal recognition to the applicant’s gender constituted an interference with his right to respect for one’s private and family life; however, it found that the interference was justified under the circumstances, due to the fact that Finland does not allow marriage between persons of the same sex (§ 49). The Section added that it was not disproportionate for Finland to have required the applicant to transform his prior marriage into a civil partnership or, should his wife refuse, to dissolve his marriage by divorce (§ 50).

As to the alleged violation of the principle of non-discrimination (art. 14), the applicant has not obtained any more success. The Section found that the situation of the applicant is not sufficiently similar in order to be compared with the situation of anyother person, including non-transgender persons and unmarried transgender persons. The applicant therefore has not established being a victim of discrimination compared to other groups of people in similar situations (§ 65).......

As the Court followed several previous precedents, it is not clear why the case was referred to the Grand Chamber. The decision of a referral is less surprising when considered from a non-legal point of view, because this type of case benefits from the particular attention of judges desiring the development of "LGBT rights." Perhaps they think that the time has come to establish a new right and to reverse the precedent of the Court? This was already the case in July 2002 with the Goodwin v. The United Kingdom case, which was also related to the right to marriage for transgender people.

In this Finnish case, the Grand Chamber could, following the case of X and others v Austria and against the ruling of this Section, consider the situation of the applicant similar to that of a non-transsexual married couple. Finland would then have the difficult task of proving that the difference of treatment between these similar situations is not based solely on the sexual orientation of the applicant, or that objective and reasonable grounds of a particular gravity justify it.

More generally, the case H. v. Finland is an illustration of the difficulties resulting from the acceptance of a double definition of sex: The objective definition which considers the biological sex, and the subjective definition, which considers the social sex. The question that arises is how to determine which of these definitions in order of priority informs the law. And even more so, when the law decides to build upon a “social sex” in order to establish a “legal sex,” different from biological sex, how far will this legal fiction produce effects? And what will become of the rights acquired under the title of biological sex? ....

This difficulty recalls that the purpose of legal fictions is not to

emancipate us from reality, through the law, but the normal function

of re-establishing concordance between the law and reality.

This is the limit of the use of legal fictions, and the difficulty of

the H. v Finland case, because the law can not emancipate itself

from reality. ![]()

If reading about this case gives you a headache, sit down and listen to a

recording of the Finlandia hymn, described in Wikipedia as “a serene

hymn-like section of the patriotic symphonic poem Finlandia, written in

1899 by Finnish composer, Jean Sibelius”. This is what I did and it fixed

the headache - some good things do come out of Finland - Babette Francis