How can we mend our

fractured society?

by John Morrissey

Over 40 years ago, approaching the steps leading up to London's British Museum, I arrested the fall of an old lady tumbling down those steps towards me. She appeared to be in pain and I noticed one finger broken off her left hand and hanging by a thread. Fearing that she might go into shock, I tried to prevent her from seeing it. Her indignant reply was: "Young man! I lived through the Blitz!"

Over 40 years ago, approaching the steps leading up to London's British Museum, I arrested the fall of an old lady tumbling down those steps towards me. She appeared to be in pain and I noticed one finger broken off her left hand and hanging by a thread. Fearing that she might go into shock, I tried to prevent her from seeing it. Her indignant reply was: "Young man! I lived through the Blitz!"

She was of course a proud member of the "Bulldog Breed". We in Australia had our own stoical breed too, you know — the 1930s Depression generation who fought or lived through World War II and went on, with the help of an outstanding migration intake, to build the country we know today.

Have we attempted anything on the scale of the Snowy Mountains Scheme since? Claims that the National Broadband Network as a digital program and for the current shambles that is the transition to renewable energy are equivalent nation-building monuments are bizarre.

But what Australia's previous generations also achieved was to build a remarkably cohesive society, which absorbed multitudes of hard-working and creative immigrants from what seemed to be every country on earth. It broke the implicit White Australia Policy, provided full employment and opportunities to prosper, educated the children, and avoided the friction that seemed to attend every other "melting pot" society across the world.

Church attendance used to be much higher than in recent years, and if sectarianism was a divisive factor, it certainly did not spring from indifferentism. The ecumenism which followed was accompanied by a decline in both faith and practice; but the most obvious demarcation between Protestant and Catholic was the peaceful co-existence of separate school systems.

Conflicts seemed to exist in faraway places, with the Cold War hotting up, participation in the Korean conflict, and even the awareness of the threat of nuclear destruction not dimming the optimism which prevailed. Perhaps the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games, which set the standard for every Games that followed, was the apogee of this success story.

Popular literature also celebrated this social cohesion. They're a Weird Mob (1957), purportedly written by Italian journalist "Nino Culotta" (real name: John O'Grady), is one example, telling of a postwar immigrant's warm acceptance into a building gang, his amusing assimilation into Australian customs and idiom, and his eventual marriage to a local girl.

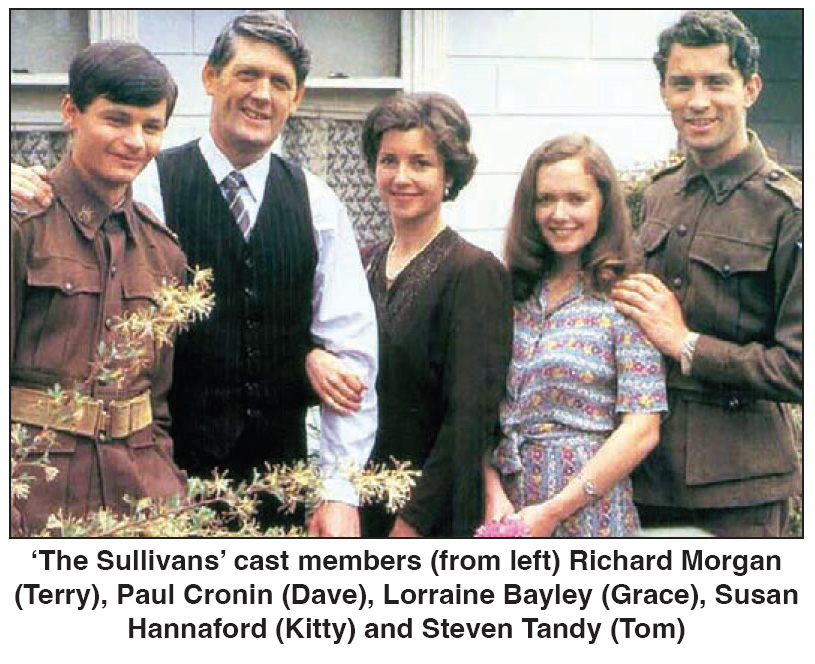

With the coming of television, local drama flourished and evolved into a swarm of "soapies" which showcased a glowing picture of life in Australia, from the nostalgia of The Sullivans, through Skippy the Bush Kangaroo and A Country Practice to the timeless saga of Neighbours. Overseas audiences were taken in by these depictions of life in Australia, and we even came to believe in them ourselves. Discussion of these "soapies" at work or school provided social common ground, as the radio serials had in the past.

What could and did go wrong? Today, no longer do primary schools begin the week with raising the flag and chanting "I love God and my country; I honour the flag; I will serve the Queen; and cheerfully obey my parents, teachers and the law." The very idea of patriotism is now taboo in all but sport, and this is reflected in the scarcity of recruits for the armed forces.

What could and did go wrong? Today, no longer do primary schools begin the week with raising the flag and chanting "I love God and my country; I honour the flag; I will serve the Queen; and cheerfully obey my parents, teachers and the law." The very idea of patriotism is now taboo in all but sport, and this is reflected in the scarcity of recruits for the armed forces.

The generic Christian religious education which was widespread until recently in government primary schools has now been deliberately crowded out. Programs which promote radical gender theory have taken their place in a crowded curriculum, under deceptive titles such as Respectful Relationships, and that of Safe Schools for secondary education.

A history curriculum replete with brave explorers, intrepid pioneers and heroic Anzacs has been over-shadowed by guilt for the wrongs done to the environment, to our Indigenous peoples and to non-whites in general, a perspective which was described by historian Geoffrey Blainey, in his 1993 Latham lecture, as "the black armband view of history".

Another misfortune is that when foundational learning was discarded, with phonics, the times tables and recitation becoming almost extinct, Australia began to slide down international rankings in education — as did most of the Anglophone world.

Paradoxically, it was Labor governments which have phased out technical education and employment, under the mantra that young Australians should all have access to a university degree, with TAFE left to pick up the pieces for those drawn to the trades.

This coincided with the "opening up" of the Australian economy in the 1980s, which led to the near demise of manufacturing, outside of food-processing. Slashing import duties crippled manufacturing, but gave Australians a higher standard of living, with what used to be luxuries now cheap imports. Flatscreen TVs now grace every living room and Mum no longer darns socks while Dad mends the kids' shoes.

It took until the past decade for the last of the local car industry to shut down, which symbolised the near death of manufacturing in Australia. Employment opportunities which had absorbed and assimilated waves of immigrants from the 1950s into the 1970s disappeared and we became a so-called "service economy", depending on mining and agriculture to pay our way in the world. Australia now has a whole class of up-to-third generation unemployed, while foreign students and backpackers fill jobs that no-one else wants to do.

In modern society, technology has proved an agent for social isolation for many, with the smart phone promoting a relationship with a screen rather than with other human beings, a situation which worsened during the recent Covid pandemic, with lockdowns and working from home further insulating people from the social contact provided by work or school. Owing to these two factors, mental illness rates, especially among children, have soared (Weekend Australian Magazine, March 30–31, 2024).

Easy access to street drugs has also been harmful to the physical, psychological and social well-being of young people. This situation has not been helped by the ambiguous manner in which drug laws have been applied, and the mixed messages conveyed by the notion of harm reduction, which has green-lighted "safe" drug use.

Families have always been the basic unit of human society, and there is little doubt that any weakening of this institution must affect the whole fabric. Non-marital cohabitation, no-fault divorce, the so-called Sexual Revolution and the rise of radical feminism can be regarded as both causes and symptoms of the decline of the traditional family.

After common law marriage attained equality with traditional marriage in the eyes of the law, and a church wedding was no longer the norm, it was no surprise when the "gay" movement decided to pursue what they had previously despised, as another step towards social and legal approval of their lifestyle. However, despite an at times bitter plebiscite in 2017, same-sex marriage was subsequently legislated quite smoothly — as the significance of marriage had already been altered — and a Pandora's box was opened, affecting children and the notion of gender.

After common law marriage attained equality with traditional marriage in the eyes of the law, and a church wedding was no longer the norm, it was no surprise when the "gay" movement decided to pursue what they had previously despised, as another step towards social and legal approval of their lifestyle. However, despite an at times bitter plebiscite in 2017, same-sex marriage was subsequently legislated quite smoothly — as the significance of marriage had already been altered — and a Pandora's box was opened, affecting children and the notion of gender.

Since at least the 1948 United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, freedom of religion has been taken for granted in Australia, so that the UN's 1981 Declaration on Religious Freedom has not even been adopted by the Australian Parliament. Nevertheless, since the year 2000 several state charters and additional federal legislation on race and sex have been introduced.

These have been weaponised to restrict traditional values and drive religion out of the town square, to become what one letter-writer to The Australian described as "just a holy huddle for an hour on Sunday morning". Some opponents of religious freedom even justify this aim by misrepresenting the principle of the separation of church and state. Historically, it means the exclusion of an established church, rather than the denial of a voice to any of the various religious denominations.

Today, with a compliant Australian Law Reform Commission, the enemies of religion are hellbent on revoking the exemptions regarding employment and enrolments provided in 2013 human rights legislation for schools conducted by religious bodies. Setting up a straw man of widespread intolerance on the part of Christian-run schools, their opponents are ripping chasms in the social fabric, relying on indifferentism among the public and a cynical federal government to carry the day. After all, allowing the Australian Capital Territory government's takeover of the Calvary Hospital in 2023 has shown exactly where the Albanese Labor government stands.

Reactions within Australian society to the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7 last year, and to events in Gaza itself, have shown up the fault lines in what we have deluded ourselves to believe is our successful multicultural society. Hundreds from the immigrant enclaves of Sydney were already celebrating the mass slaughter and kidnapping of Israelis, even before the first retaliatory shot had been fired against the Hamas regime in Gaza.

Anti-Semitism reared its ugly head, especially in Australian universities, where Jewish students were made to feel unsafe. What can only be described as hate speech has been spewed out with impunity in many mosques, while under the banner of "Free Palestine" neo-Marxists and other self-styled progressives have taken to the streets.

The response of state and federal governments has been at best equivocal, accompanied by the usual stern lectures against imagined Islamophobia as well as anti-Semitism. Instead of police protecting Jewish people in public, in both Sydney and Melbourne, they have kept the peace by removing them, citing their very presence as provocations to the mob.

The cynicism with which many regard politics is a serious problem. When the Albanese government reneged on its repeated expressions of support for "Stage 3" income tax cuts, it seemed that voters did not turn a hair. Similarly, the moral gymnastics required to view Israel and Hamas as equally to blame for the current conflict defies the imagination. Perhaps the claim that we now live in a post-truth world absolves political leaders of culpability for their deceit, as Niccolò Machiavelli argued 500 years ago, but the proposition sits oddly with the same government today legislating fines for misinformation and disinformation.

It would be easy to blame politicians for much of our social dysfunction, but politics is always downstream from culture, as ever-present social media and opinion polls purport to tell them which way the wind is blowing.

For much of 2023 Australians were divided by a campaign on a referendum which in effect was to give the federal government a blank cheque, enshrined in the Constitution, for separate powers regarding Indigenous Australians. The contest was bitter, with the morality and motives of those on the "No" side impugned as racist and hard-hearted. Despite an asymmetrical battle, with massive public and corporate resources thrown behind the "Yes" case, the appeal of two articulate and sincere Indigenous opponents, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Warren Mundine, saw two-thirds of Australians rejecting the proposal. Yet the scars remain, and unrepentant Labor state governments persist with their "Truth and Treaty" machinations regardless.

What is often forgotten is that while politics is downstream from culture, culture is downstream from religion, which has infused it from the beginning of human society. It has provided the glue to bind civilisations with a shared ethic. Judeo-Christian values, which have been the foundations of Western culture, are rapidly being eroded today. Queer Studies are taught in degree courses in Australian universities which have rejected the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation's offer to fund courses in the history, literature, art, music and philosophy which are our heritage.

Nevertheless, these same universities have accepted funding from China for Confucius Studies and from Saudi Arabia for Islamic Studies. Among the majority of Australians today there is a lack of even knowledge of our roots, while a minority are actively engaged in expunging them by stifling debate through speech code and cancel culture, not to mention destroying symbols such as historical statues, which goes a long way to explaining the plight we face.

In an address to the National Symposium for Classical Education, held in Phoenix, Arizona, on March 21, Australia's former prime minister Tony Abbott spoke up for our heritage of Western civilisation (The Weekend Australian, March 30-31, 2024). He also hailed the advances in human freedom, prosperity, health and living standards which have occurred across the globe in recent decades, in contrast to the gloomy perspectives forced on the young today.

In an address to the National Symposium for Classical Education, held in Phoenix, Arizona, on March 21, Australia's former prime minister Tony Abbott spoke up for our heritage of Western civilisation (The Weekend Australian, March 30-31, 2024). He also hailed the advances in human freedom, prosperity, health and living standards which have occurred across the globe in recent decades, in contrast to the gloomy perspectives forced on the young today.

Abbott also expressed his gratitude for the training he received at school and university, especially the Oxford tutorial system, which went beyond receiving information to assimilating knowledge and adopting and defending a position. He argued that education, and especially a knowledge of history, can play a large part in the formation of character and judgement. Reading and re-reading of the New Testament he especially advocated, as it is the foundation of our culture and has shaped our moral and mental universe.

Even if one doesn't attend church, the knowledge of our shared Western heritage is necessary for confidence in our own identity and that of our society. Decline of patriotism is inseparable from the lack of knowledge of our civilisation or any conviction that it is worth defending. If the young grow up being fed on the ephemera of the small screen, alienation and self-loathing of their own society, how will they face up to the external challenges which the free world faces today from the rise of totalitarianism?

Given the grip that atheist and nihilistic forces have on culture, education and politics today, it is doubtful whether Tony Abbott's ideal can be realised, outside of the rare institution of Sydney's Campion College and the numerous Christian schools and colleges, conducted by evangelical Christian groups, but attracting many from outside their congregations. Both the Catholic system and independent schools have to a large extent compromised with secular authorities and allowed them to impose their sterile national curriculum, with its politically-correct preoccupations with Asia, Indigenous issues and environmental sustainability.

A recent Census found fewer than 50% of Australians self-identifying as Christians and growing numbers in the "no religion" category. Immigrant enclaves in many parts of Sydney and Melbourne are failing to integrate, let alone assimilate. Although this has been evident since the turn of the century, it is now undeniable.

What is the best way for Christian families and faith groups to survive the new barbarian invasions intact? Many have found consolation and practical guidance in the writings of American commentator Rod Dreher, author of two bestselling books, The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation (2017) and Live Not By Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents (2020).

His strategy has often been described as "circling the wagons" — a term he has rejected as a misrepresenting what he has advocated (although it is noteworthy that in 2022 he emigrated from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to settle in Budapest, Hungary).

A more accurate analogy of Dreher's Benedict Option is the pre-flight safety instruction given to airline passengers: "In the event of an emergency it is important to fit your oxygen mask first before you try to help others around you."

Dreher wants Christians to resist being catechised by the hostile culture that surrounds them. They can only do this by forming strong communities based on the oxygen of orthodoxy (i.e., the Holy Spirit), otherwise they will be powerless to witness and minister effectively to the populations around them.

In this constructive way, we must not yield the public square to the enemies of Western civilisation, but make our voices heard, as neighbours, colleagues, voters and members of political parties and community groups. Jesus calls on us to be the "salt of the earth" (Matt 5:13).

We can express our values, as the early Christians did, by the example of our lives. We can write to newspapers and call in to talkback radio. We can be forces for good in healing the fractures in our society by supporting and volunteering for charities like St Vincent de Paul and others like the Salvation Army whose members work at the coalface.

Best of all, we can adopt the adage attributed to the fifth-century St Augustine of Hippo, "Pray as though everything depended on God. Work as though everything depended on you."

John Morrissey is a retired secondary school teacher who has taught in government, independent and Catholic schools. He lives in the Melbourne suburb of Hawthorn with his blue heeler, Missy.![]()