Why the Morrison government fell by John Morrissey

As millions of Australians watched the Liberal seats falling like

ninepins that evening on May 21, it was not the defeat but its

scale which was the surprise, after predictions of a close result.

The Coalition had trailed in the polls, two-party preferred, for

two years after narrow squeaks in 2016 and 2019 and surely

could not expect another miracle.

As millions of Australians watched the Liberal seats falling like

ninepins that evening on May 21, it was not the defeat but its

scale which was the surprise, after predictions of a close result.

The Coalition had trailed in the polls, two-party preferred, for

two years after narrow squeaks in 2016 and 2019 and surely

could not expect another miracle.

Labor's hollow victory, with a record low base vote, was partly the result of an electorate which had tired of listening to Scott Morrison, as it had John Howard in 2007; but there were many factors contributing to what became a rout.

To many traditional Liberal voters it seemed that the party had deserted its base, by rolling over to compromise on progressive policies, especially on climate change and energy. This had also alienated some who had been allies in 2019, and splintered the centre-right vote. Along with the relentless character assassination that Morrison had suffered for over two years and the rise of supposed independents, the perception of a tired and flawed government took hold.

From the time of Morrison's ill-fated family holiday late in 2019, coinciding with serious bushfires, he has been unfairly beset with accusations of dereliction of duty, regardless of where responsibility lay, and members of his ministry have also been targeted, with the departure of some becoming prize scalps for their opponents in the parliament and the media.

As journalist Chris Kenny of The Australian put it, "Morrison made his mistakes but was torn down largely by concocted attacks about events beyond his control — bushfires, floods or even alleged sexual assaults." To make matters worse, Attorney-General Christian Porter and Education Minister Alan Tudge were lost to his front bench by the same agency of #MeToo, which had already brought down other prominent men, regardless of "no proven guilt".

To a government which had protected the nation from the pandemic with the early closing of external borders (against the advice of the World Health Organisation), saved a million Australians from unemployment with JobKeeper, and provided a raft of supports for business, this rejection must have seemed like the ingratitude of a feckless electorate.

Yet the formation of a National Cabinet was a singular error. There ensued a breakdown of Australia's federation, with state premiers and their chief health officers going their own way, and the Commonwealth seeming powerless to do anything but pick up the bill.

Although the Labor opposition seemed sidelined, its approval of government action to address the pandemic, with only occasional sniping, allowed it to remain a small target. Meanwhile, Labor premiers used their constitutional power over health matters to make disproportionate responses to the pandemic, which damaged livelihoods and infringed on the liberties of citizens in a myriad of ways. The Morrison government was to bear the blame for neither standing up for the Australian people by curbing these excesses, especially the closing of state borders, nor explaining the division of powers under the Constitution which tied their hands.

In 2019 it had been the northern Queensland vote, and swings in seats where workers in mining and energy had put their trust in the Coalition, which had saved the government. Clive Palmer had spent over $80m in what was essentially a negative media campaign against Labor and the Greens, and Pauline Hanson's One Nation Party had also implicitly supported the Coalition. With the advent of a professed Evangelical in PM Scott Morrison, Christians also had high hopes for legislation to protect freedom of religion from a raft of anti-discrimination laws enacted under the Gillard Labor government.

After the Coalition's failure to delete Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act in 2014-15 and during the samesex marriage campaign, it became evident that human rights legislation threatened the freedom of faith-based schools and other institutions to operate according to their respective ethos.

When in early 2022 the Coalition's much delayed and quite restrained legislation to protect religious freedom was withdrawn on account of opposition in the Senate and dissent among Liberal MPs, many felt a sense of betrayal after the undertaking by the Coalition government to keep faith with believers. In the event, the Australian Christian Lobby encouraged its supporters to vote against five Liberals who opposed the Bill, which may have contributed to them all losing their seats.

However, the key event occurred in October 2021, when the Liberal party room decided to embrace the target of net zero emissions by 2050, without resiling from its Paris commitment to a reduction of 28 per cent by 2030. This was in response to global financial pressures and what appeared to be an electoral imperative.

Thus the Prime Minister, who as Treasurer had brandished a

lump of coal in Parliament in 2017, was seen to have surrendered

to climate change activism when he committed Australia to this

benchmark while attending the UN Climate Change conference

(COP26) held in Glasgow. In spite of this late conversion, he was

depicted as a pariah in much of the local media while attending

this hypocritical gathering, with its hundreds of private jets and

other extravagances. Labor then neatly trumped this concession

by announcing a goal of 43 per cent emissions cuts by by 2030.

Thus the Prime Minister, who as Treasurer had brandished a

lump of coal in Parliament in 2017, was seen to have surrendered

to climate change activism when he committed Australia to this

benchmark while attending the UN Climate Change conference

(COP26) held in Glasgow. In spite of this late conversion, he was

depicted as a pariah in much of the local media while attending

this hypocritical gathering, with its hundreds of private jets and

other extravagances. Labor then neatly trumped this concession

by announcing a goal of 43 per cent emissions cuts by by 2030.

While the National Party held all its seats, the Liberals certainly suffered from the revenge of Clive Palmer, Craig Kelly (marginalised by the party for his views on Covid treatment) and probably Pauline Hanson as well. The billionaire Palmer spent even more than in 2019 on a media storm, damning the Liberals along with Labor and the Greens. His United Australia Party gained very little from its campaign, but received nearly 800,000 votes across the nation, without any strong preference flow to the Liberals, unlike the Greens whose disciplined preferences allowed Anthony Albanese's Labor Party to govern in its own right.

After starting 2022 with two adverse redistributions and the WA Premier Mark McGowan factor rendering Coalition losses in that state unavoidable, the Morrison government struck further trouble in NSW.

It started with Liberal Senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells questioning Scott Morrison's truthfulness. Then the polarisation between the party's conservatives and so-called moderates became obvious. It transpired that the selection of Liberal candidates had been delayed in up to 12 seats, so that, with only weeks to go, candidates could not be elected by the membership, as decided at an earlier state conference.

The "moderates" had succeeded in this; but Morrison forestalled their plans by installing a number of his own candidates, giving rise to allegations of "captain's picks". Then we had the glaring spectre of disunity displayed when "moderate" NSW Deputy Premier Matt Kean attacked one of these picks, endorsed Liberal candidate Katherine Deves, for her principled defence of women athletes against unfair competition from transgender "women" (i.e., biological men). The damage done to the party by this factionalism has more recently been highlighted on ABC television (Four Corners, July 4).

An interest rate rise in the final weeks of the election campaign did not help either. But for the Morrison government, the "teal"

phenomenon of a handful of apparently cleanskin professional

women, posing as independents, was the

final straw, as it deprived the Liberals of a

number of blue-ribbon seats.

did not help either. But for the Morrison government, the "teal"

phenomenon of a handful of apparently cleanskin professional

women, posing as independents, was the

final straw, as it deprived the Liberals of a

number of blue-ribbon seats.

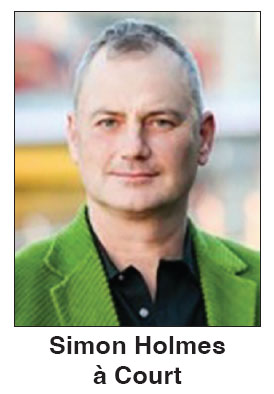

Well resourced by Simon Holmes

à Court's Climate 200 fund and local

activists, these women received heavy

support from female voters, who embraced

their slogans on trust, in lieu of actual

policies, and responded to the misogynist

image of Scott Morrison cultivated by his opponents. We should be thankful that this group does not hold the balance of power

which it sought in the House of Representatives.

be thankful that this group does not hold the balance of power

which it sought in the House of Representatives.

In all, the fall of the Morrison government was a result of the implacable opposition of those who believed that they had been cheated of victory in 2019, the distractions of the pandemic which cost them their strongest suit in better economic management, and their failure to hold the line on issues such as climate change, energy and religious freedom.

Furthermore, throughout the election campaign the Coalition leaders merely stood on their record of achievement relative to other nations, which fell on deaf ears, no matter how unjust this seems. In contrast, the Labor opposition claimed to have a vision, conveyed by the assurance that "We have a plan …", improbable as their published policies appeared to thinking Australians.

After his underwhelming performance during the campaign, Anthony Albanese appears to be growing into the role of Prime Minister in his appearances overseas, at least through the lens of the local media, which are giving the new government a honeymoon period seldom enjoyed by the Coalition.

At home the story is different, with a downturn in the economy, while Labor charges ahead with its climate-change policies, imposing contradictory demands on base-load energyproviders and ignoring signals from overseas that it is time for a rethink.

John Morrissey is a retired secondary school teacher who has taught in government, independent and Catholic schools. He lives in the Melbourne suburb of Hawthorn.

![]()